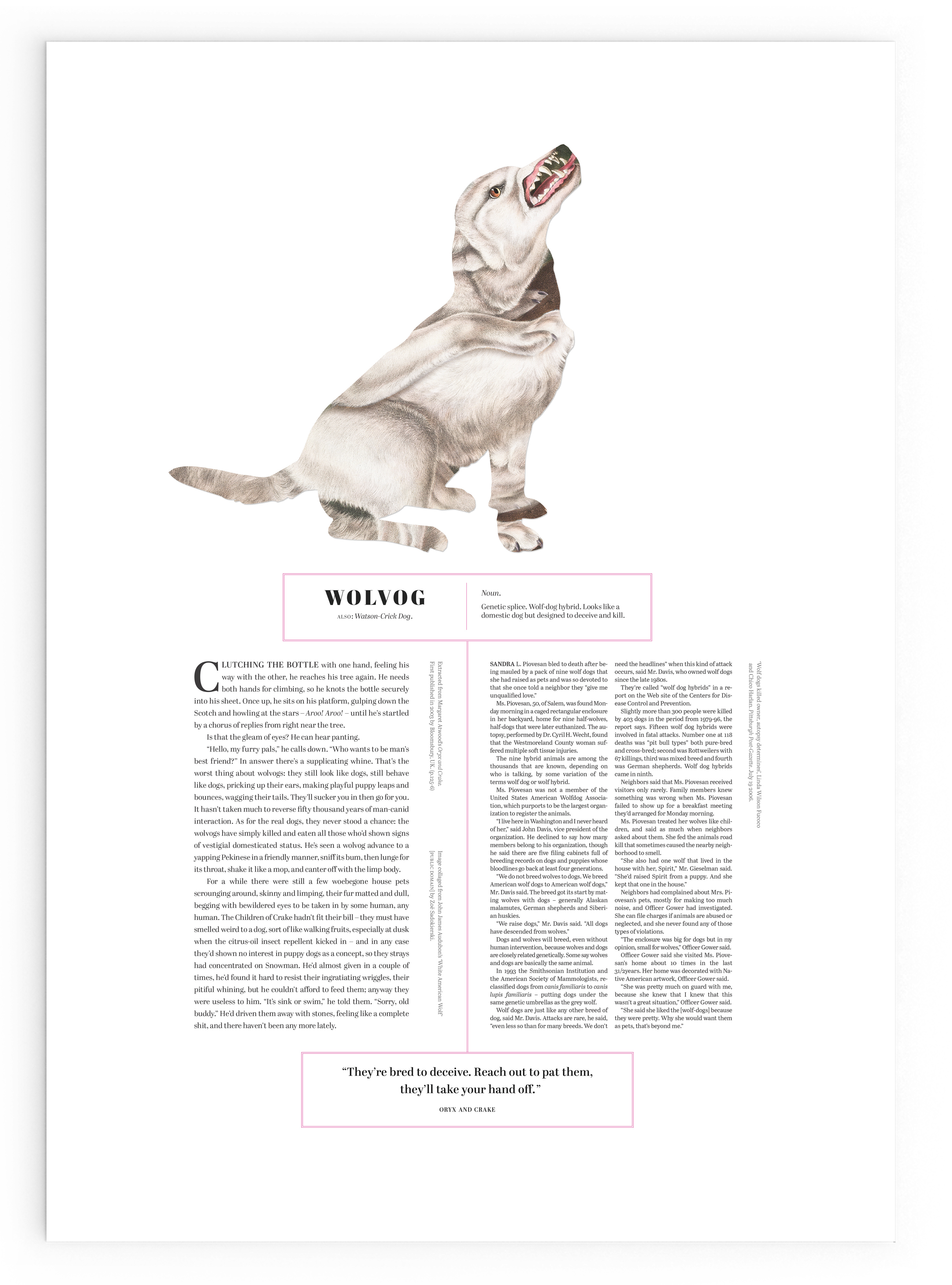

Margaret Atwood’s Maddaddam trilogy is set in a near-future post-apocalyptic age, in which anthropogenic climate change and bio-engineering have catastrophically altered the earth’s ecosystem and inhabitants. As Atwood tells it, humans are directly responsible for mass extinction of plant and animal species, and have unleashed genetically modified creatures that evolve in unexpected ways. Rabbits injected with jellyfish DNA glow softly at dusk. Wolf-dog hybrids bred for military service obliterate domestic dogs and hunt humans. Pigs spliced with human stem cells, an experiment in growing organs for human transplants, launch tactical attacks and communicate in a kind of language. Yet the most frightening aspect of Atwood’s vision is that it is based on real-world science. In the postscript to Maddaddam, Atwood says her speculative fiction: does not include any technologies or biobeing that do not already exist, are not under construction, or are not possible in theory.

‘The Everything Change’ is a series of mixed-media collages which visually interpret key ideas from Atwood’s trilogy, juxtaposed with scientific information drawn from journal articles and news reports. These collages marry Atwood’s fiction with the real world science it is based upon, in order to draw attention to the way these different genres – fiction and science journalism – address urgent ecological issues. How might such ‘genre blending’ images visually communicate the complex entanglements that arise from humans meddling in the natural world? How might ambiguous images be used to facilitate transdisciplinary conversations about transitioning away from anthropocentric understanding the world?

I created a suite of Atwood’s hybrids, using a hybrid print-making technique: risograph prints, sliced and collaged back together in layers, pressed ‘chine collé’ style on an etching press. These are all A3 size (and for sale, please contact me directly).

Catalogue Essay:

I think calling it climate change is rather limiting. I would rather call it the everything change because when people think climate change, they think maybe it’s going to rain more or something like that. It’s much more extensive a change than that because when you change patterns of where it rains and how much and where it doesn’t rain, you’re also affecting just about everything.You’re affecting what you can grow in those places. You’re affecting whether you can live there. You’re affecting all of the species that are currently there because we are very water dependent. We’re water dependent and oxygen dependent.

Margaret Atwood,

interview with Ed Finn,

Slate, Feb 2015.

Aside from climate change itself, the greatest challenge environmental scientists face is engaging an increasingly apathetic public. Despite decades of mainstream scientific evidence that anthropogenic climate change poses a severe threat to the planet and its inhabitants, many people still don’t believe anything can or should be done about it. Psychologist Per Espen Stoknes describes a ‘psychological climate paradox’ in which concern for climate change in wealthy democracies falls as the scientific evidence mounts. His book What We Think About When We Try Not To Think About Global Warming (2015) presents five psychological barriers contributing to this paradox: distance, doom, dissonance, denial and identity. The central problem for current climate science communication, Stoknes says, is that it triggers each of these barriers. Like many other scholars, scientists and journalists addressing the climate paradox, he identifies an urgent need for alternate narratives about climate change which aim to rouse us from our inertia in order to trigger widespread preventative action.

One way scientists are addressing climate change apathy is by embedding human narratives into empirical information visualisations. One example comes from Professor of Biology Lesley Hughes, who altered a well-known graph of rising global temperature over the next hundred years by adding three lines: ‘me, my children, my grandchildren?’ This simple alteration, with its anxious question mark, puts the distance of decades into terms we can empathise with. This altered graph represents a new approach to climate change communication in which scientists recognise the value of extending quantitative data with qualitative information. Or, as science communicator and analyst Ketan Joshi puts it in a 2017 article for The Guardian: ‘it’s time to build a bridge between data and emotion.’

Human narratives are also being used to address climate change through climate fiction (cli-fi) which deals with the possible consequences of ecological issues through immersive, fictional scenarios. Many cli-fi authors† underpin their fiction with extensive scientific research, creating plausible speculations for readers to explore through the lens of characters, as they move through possible environmental, political and psychological consequences of anthropogenic climate change. Critics and authors advocate cli-fi as a gateway for readers who don’t usually engage with science, making environmental issues more personal and less obscured by political and scientific jargon.

Comparing the two approaches, ‘emotive’ scientific visualisations have the advantage of immediacy; the visual form of a diagram or chart takes little time to decipher, packing an instant punch. Yet through their conventional graphic language, these visualisations still read as representations of ‘what is to be’ and allow little opportunity for speculation or hope. Cli-fi novels demand longer attention and a willingness to engage in genre- fiction but reveal more nuanced arguments and narratives.

Margaret Atwood’s Maddaddam trilogy—Oryx and Crake (2003), Year of the Flood (2009) and Maddaddam (2013)—is set in a post- apocalyptic near-future in which human-induced climate change and bioengineering have catastrophically altered the earth’s ecosystem and inhabitants. Humans are directly responsible for mass extinction of plant and animal species and have unleashed genetically modified creatures that evolve in unexpected ways. The most frightening aspect of Atwood’s vision is that it is based on real-world science. Atwood says her speculative fiction ‘does not include any technologies or biobeing that do not already exist, are not under construction, or are not possible in theory.’

The series of ’speculative diagrams’ exhibited here visually interpret key ideas from Atwood’s trilogy, juxtaposed with scientific information drawn from journal articles and news reports. These diagrams marry Atwood’s fiction with the real world science it is based upon in order to draw attention to the way these different genres—fiction and science journalism—address urgent ecological issues.

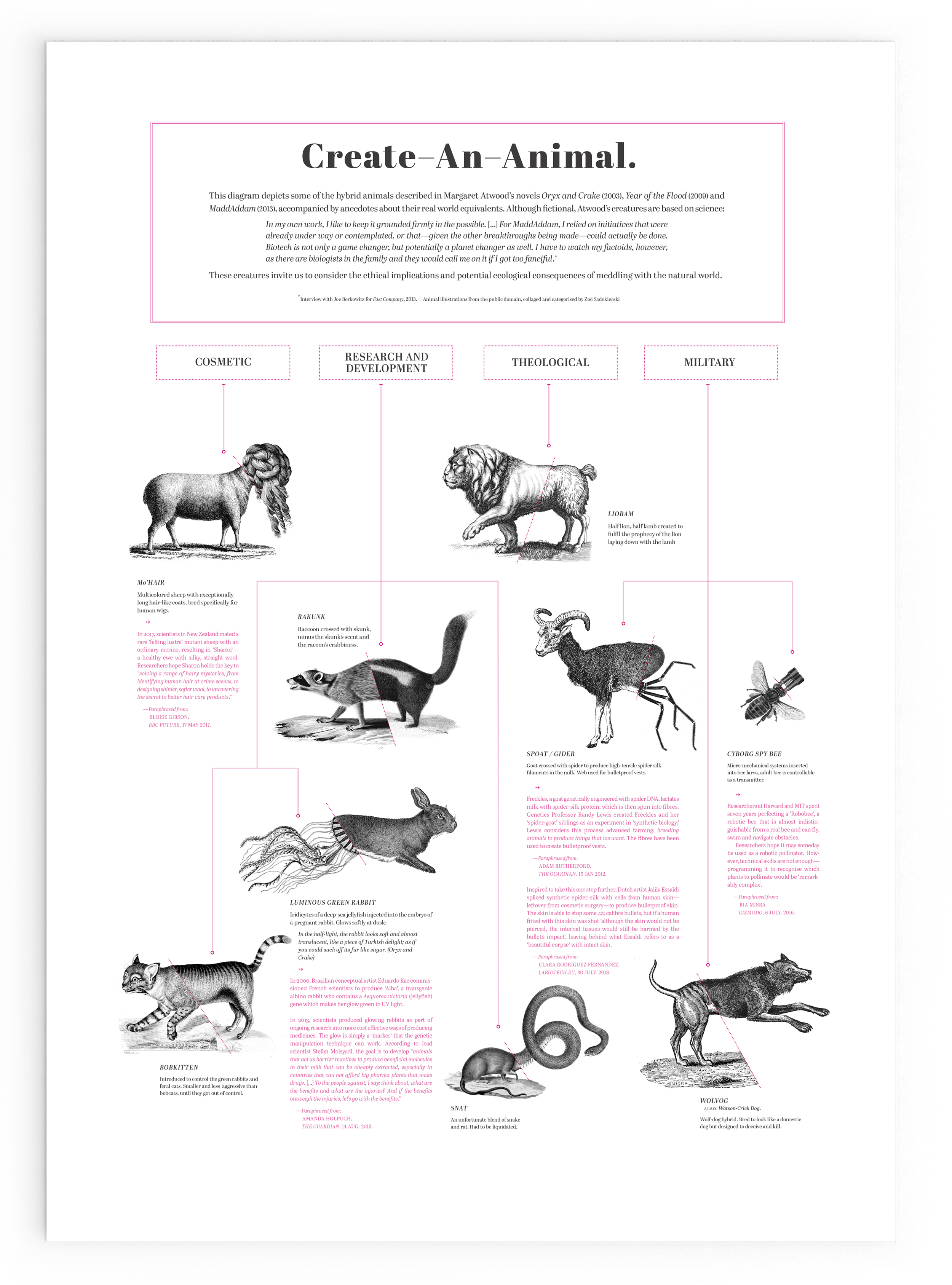

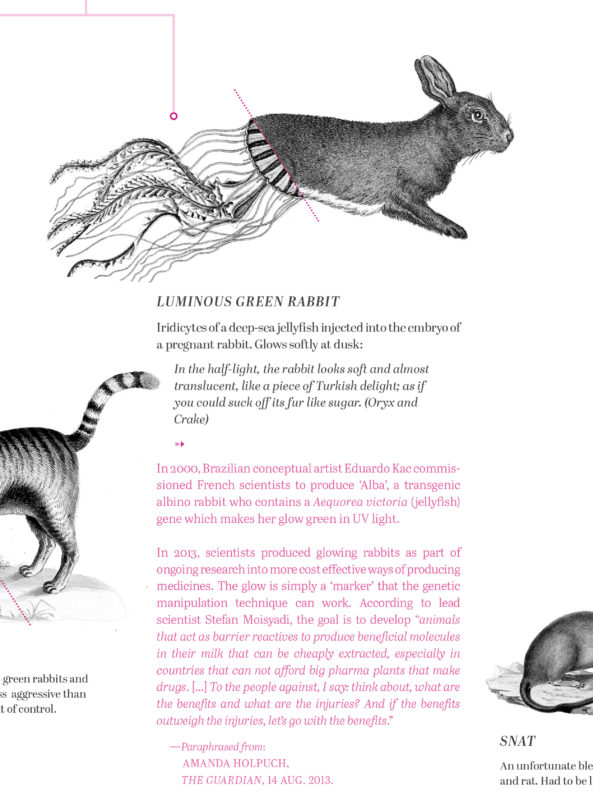

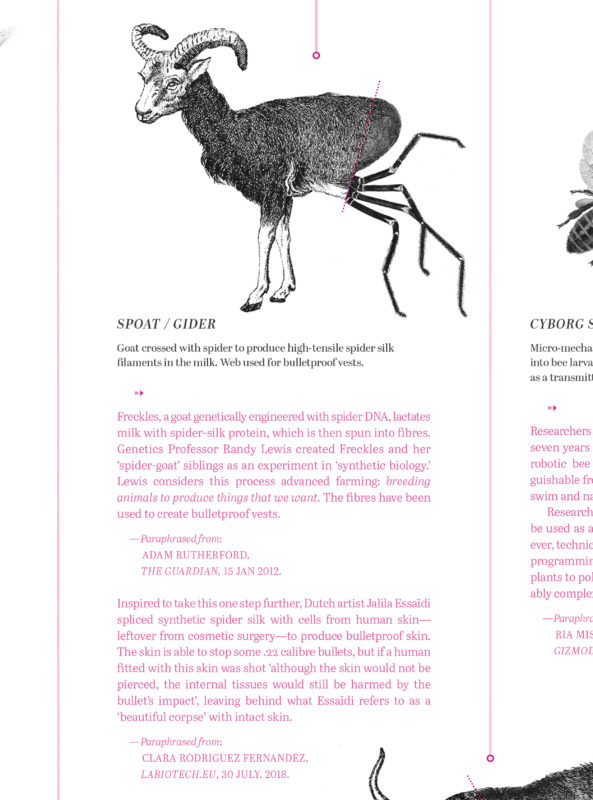

For example, ‘Extinctathon v. 2019’ charts every animal mentioned in the trilogy, overlaid with the IUCN conservation status of each creature in 2019. A set of specimen charts depict three of the genetically modified creatures from Atwood’s trilogy —a pigoon, a wolvog and a luminous rabbit—accompanied by reports of the ethical and environmental consequences of similar real-world genetic experiments.

Meanwhile, courage: homo sapiens sapiens sometimes deserves his double plus for intelligence. Let’s hope we are about to start living in one of those times.

—Margaret Atwood, ‘It’s not climate change, it’s everything change’, Medium. 2015.

…..

† Blogger Dan Bloom is credited with coining the term ‘cli-fi’. When Atwood re-tweeted him, the term went viral. Bloom is adamant cli-fi is a unique literary category, not a sub-genre of sci-fi. Some authors reject their work being labelled cli-fi; on his blog James Bradley describes it as ‘a term that has some utility as a marketing category but seems to occlude more than it reveals when deployed as a critical tool.’ Atwood prefers ‘speculative fiction’.

At the exhibition, I shared my reading list and provided a blank A1 poster and with sticky notes for visitors to leave reading suggestions. Here is a link to a Google spreadsheet with my list and suggestions (that I found relevant to this work): https://tinyurl.com/yypql5bx