For about three years I made almost daily ‘visits’ to a troupe of wild monkeys in the Nagano region of Japan, via a live webcam that updates every minute. When I needed a moment of calm at the computer, I would tune into our primate cousins soaking in an onsen (thermal hot spring). I can’t remember how I found the site, or explain exactly why I find it so meditative, but I have a folder with over 300 screen grabs of the monkeys going about their business:

In January 2012, I traveled to the other side of the screen. Jigokudani, or ‘Hell Valley, is named for the plumes of steam rising off the thermal water. ‘Snow monkeys’ – macaca fuscata – are native to Japan. They are found across the country, but hot-tubbing is unique to the Hell Valley troupe. Reaching the monkey onsen involved hiking 1.6km through a mild blizzard (-15C). The area is a forest, not a zoo.

The anecdotes, photographs, drawings and video from this experience are the foundation of a visual narrative that explores my fascination with these creatures.

The exhibition of works on paper and artist books included: 6 water colour illustrations on Okawara (handmade Japanese) paper, 170 x 340mm; 5 paper collages, various sizes and materials; 12 framed digital photographic prints on archival paper, 254 x 510mm; 2 artist books (each an edition of 3), and; one handmade catalogue (edition of 3).

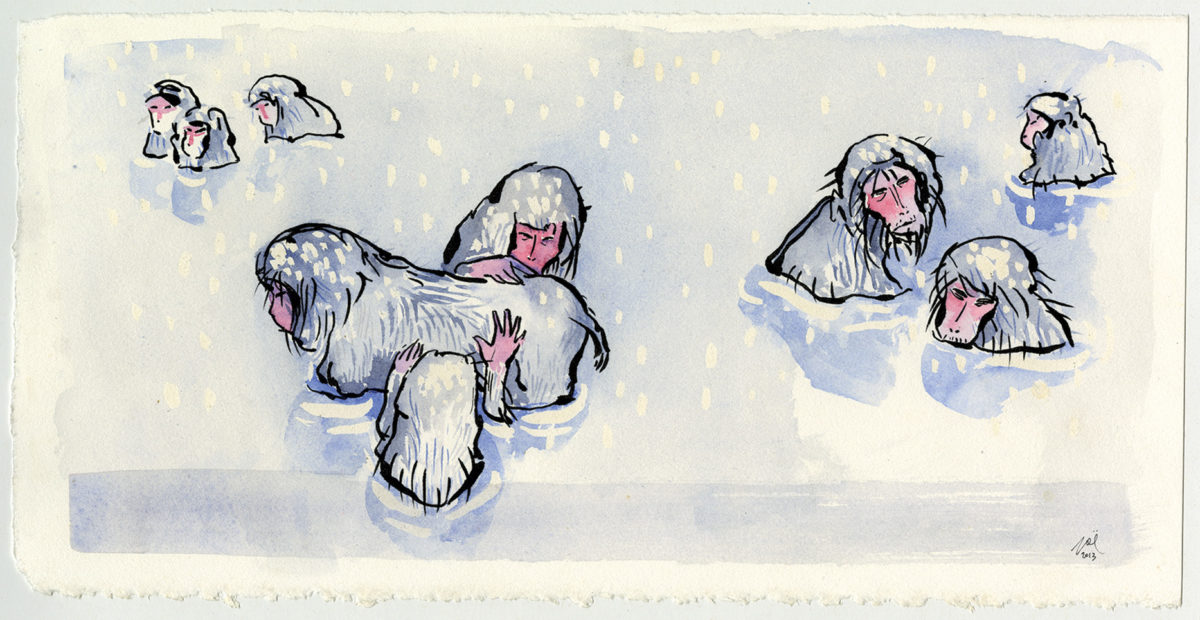

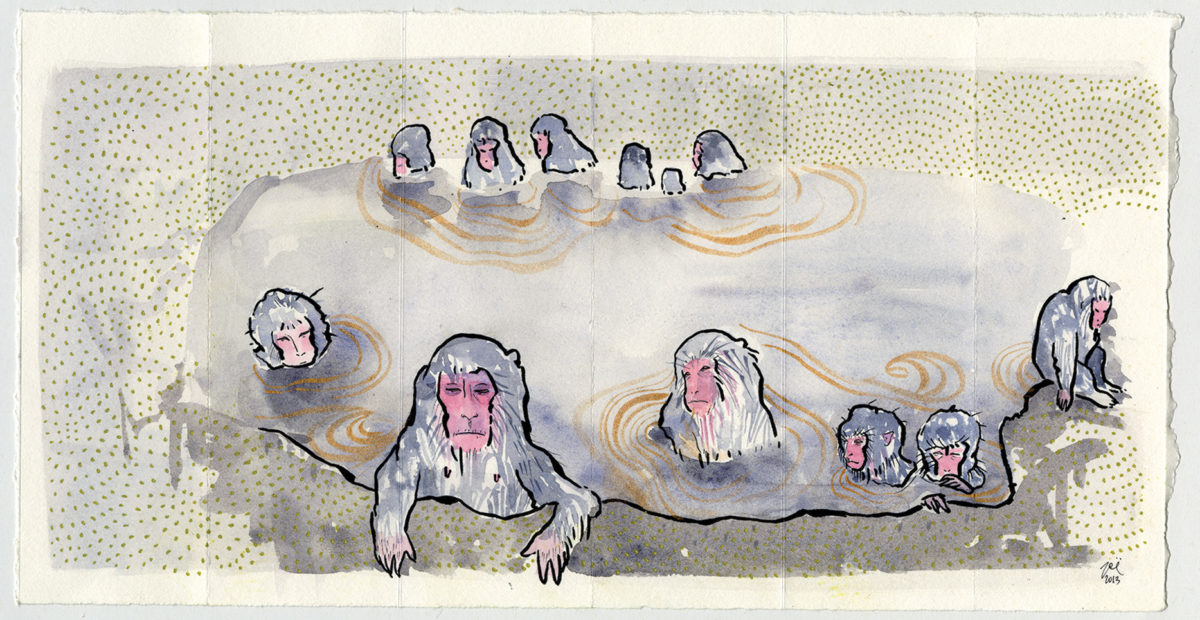

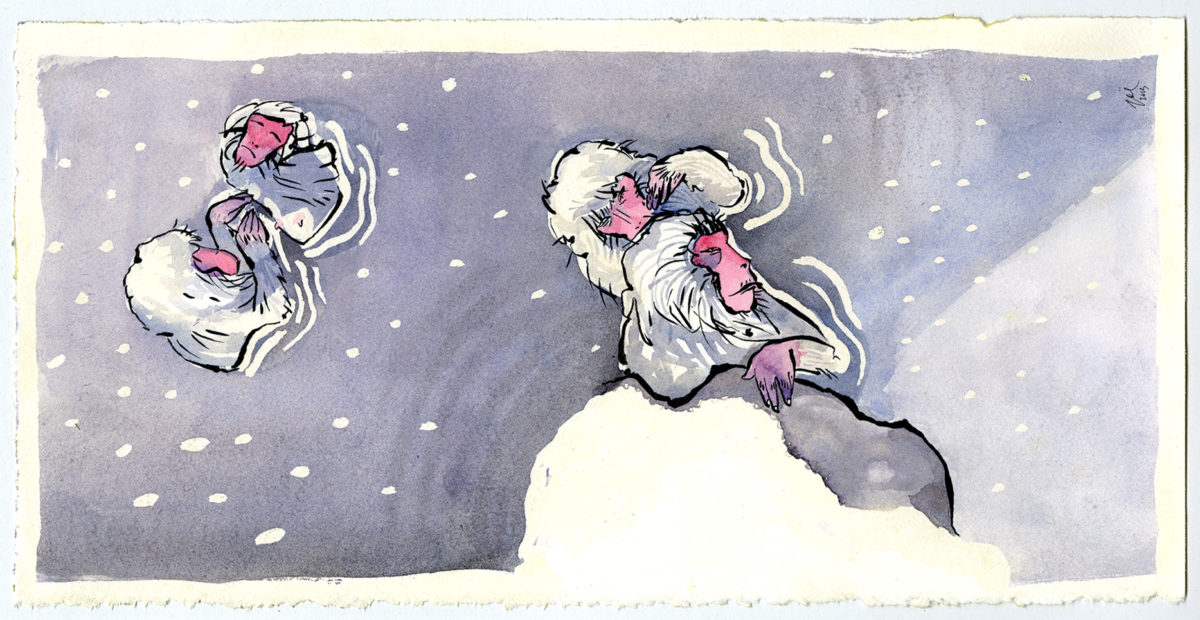

Brush and watercolour illustrations, experimenting with sumi-e inspired linework:

Cut paper collages:

Photographic collages of the macacs moving around the mountain:

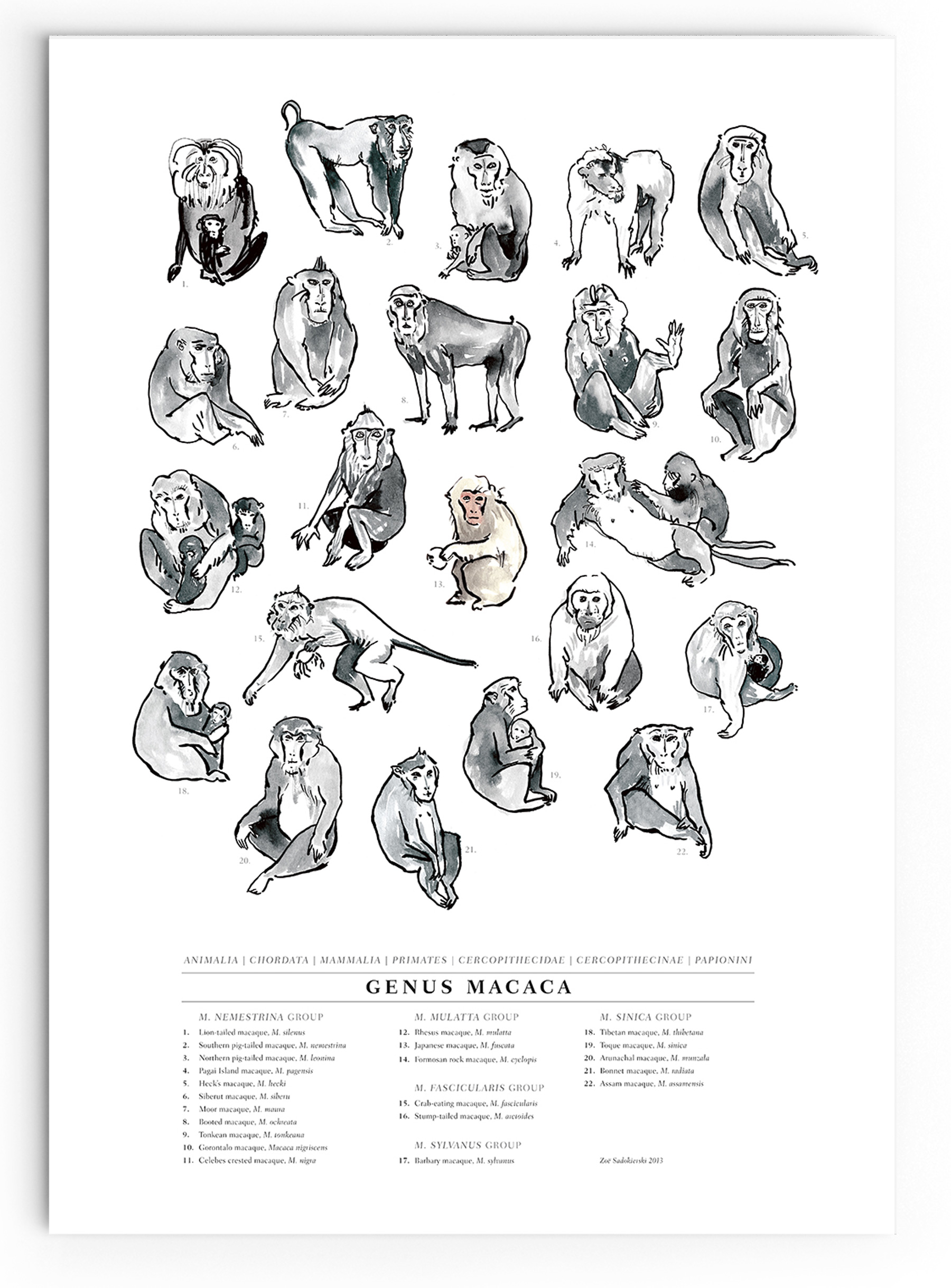

A family tree of the genus Macaca (snow monkey dead centre):

Catalogue essay:

I don’t think of myself as an artist. I am a designer. Sometimes my design practice is commercial – a client gives me a brief and pays me to design something for them. Other times, my practice is experimental – there is no client, I produce work because I am driven to. Curiosity drives my experimental work. There are questions I suspect I can answer by making things, thinking about making things, and talking about making things. In academic terms, this is practitioner-research, or practice-led research.

The work in this exhibition was created in order to experiment with ways materiality and different mark-making techniques can impact visual communication. To do so, I made a series of collages and illustrations, with specific material constraints:

- I created collages using only ‘authentic ephemera’ – paper, brochures, postcards, chopstick wrappers and other ephemeral material that I collected while in Japan. Does the graphic look and feel of Japanese ephemera lend these collages a particularly Japanese feel? How does working with this ephemera influence the way I compose the collages?

- I created a series ink and watercolour experiments mimicking the line work used by sumi-e painters, to evoke a sense of place, based on mimicking a graphic style associated with that place.

Although I enjoyed the process of creating these collages and drawings, I grew restless with the lack of narrative driving the work. They were experiments in form (depicting the monkeys and their environment) and material (paper collage, brush pen and watercolour), but lacked meaning beyond these formal and material aspects. Although these experiments allowed me to reflect on how I use materiality in my design process, they did not produce insights about how materiality might affect the visual communication of an idea or message. I was illustrating a theme/topic (snow monkeys), but not a concept (what about the snow monkeys?).

I began reading about the role of monkeys in Japanese mythology and culture. I came across Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney’s research into the monkey metaphor as a reflexive symbol of the Japanese people in her book The Monkey as Mirror: Symbolic Transformations in Japanese History and Ritual (1987). Ohnuki-Tierney explains that the way the monkey has been perceived as a metaphor has shifted, from the medieval period, where the monkey was seen as a sacred mediator between the deities and humans, to the Early Modern period when the monkey became a scapegoat figure, delineating differences between humans and the animal world, to contemporary Japan where the monkey plays the role of the clown, or trickster.

Throughout history, the monkey has been an important and complex metaphor in Japanese culture. It is the animal considered to be most similar and therefore closest to humans. Its very proximity as perceived by the Japanese has made it in turn a revered mediator during early periods in history and a threat to the human-animal boundary in later periods, fostering ambivalence that is expressed by mocking the animal. As a mediator, it harnessed the positive power of deities to rejuvenate and purify the self of humans. However, seeing a disconcerting likeness between themselves and the monkey, the Japanese also attempt to create distance by projecting their negative side onto the monkey and turning it into a scapegoat, a laughable animal who in vain imitates humans. The monkey as scapegoat is best expressed in the contemporary Japanese ‘definition’ of the monkey as ‘a human minus three pieces of hair’. By shouldering their negative side, the monkey cleanses the self of the Japanese. As a scapegoat, it marks the boundary between humans and animals. Both as a mediator and a scapegoat, the monkey therefore has played a crucial role in the reflexive structure of the Japanese.

—Ohnuki-Tierney, 1987

Ohnuki-Tierney’s writing helped me understand the monkeys in a different light, particularly the feeding ritual at Iwatayama Monkey Park and the performing monkey waiters. This exhibition is subtitled ‘Part 1’ because I’m not done with the monkeys or these material/media experiments yet. This feels like the beginning of a much longer process. Which is half the point of pushing myself to follow through with experimental practice.

I aim for this next phase to include collaboration. The flip-books included in the exhibition were created in response an animation Chris Caines made, using the screenshots I’d saved over several years of fanatic live-cam viewing. Visiting the Page Screen studio while I was producing the work for this show, Chris became interested in the monkeys – or, more specifically, my obsession with the monkeys. Animating these screen shots is a start of a collaborative project that will hopefully take us to Japan, armed with more recording equipment than I’m capable of dealing with alone.

In the meantime, there is plenty of visual experimentation and reading on the history embedded in monkey park feeding rituals and the culture of monkey performance to be done.