Conversations about artists’ books with Steve Clay, Johanna Drucker, David Senior, Shana Agid

These conversations took place in 2015, when I was on a professional development program which allowed me to travel to NYC and LA to meet with people working in the book art / artist book field, as well as conduct research into artists’ books at the MoMA Library. This content was originally posted on a blog ‘The Book Is’, which has since been incorporated into this site.

Steve Clay

Steve Clay

GRANARY BOOKS

Thursday 26 March, 2015

I’ve been reading Granary’s books since I was an undergraduate student. Until I bought a copy, Johanna Drucker’s The Century of Artists’ Books cost me a lot in overdue fines. More recently Steve Clay and Jerome Rothenberg’s A Book of the Book has been a kind of research bible as I move toward understanding the amorphous world of artists’ books.

Beyond publishing books, Granary has been a fulcrum in the NYC small press scene for nearly 30 years, holding exhibitions of artist’s books, hosting events and bringing together writers and artists to produce collaborative books. Granary also works with artists, writers and publishers to ensure valuable literary/artists’ archives end up in important institutional libraries, and initiated the Thread Talks series (including one with Australian poet and bookmaker Alan Loney, whose latest book is about to be published by Cordite with a cover I designed). I was feeling slightly nervous about meeting Granary’s founder Steve Clay, so reading Elliot David’s effusive article just beforehand did nothing to quell my nerves; it begins:

Steve Clay knows everything: Ask him. Anything. Ask him anything about the history of the small press: its manufacturers, distributors, spine binders, font designers and content providers. Ask him about poetics on film, semiotics collectives, brushless painters, the conductors of orchestral space concepts. Ask him about your grandmother’s diary entries re: your grandfather’s erectile dysfunction. Ask him, and he’ll tell you what you want to know, speak it softy and with the humble generosity of an unpretentious encyclopaedia.

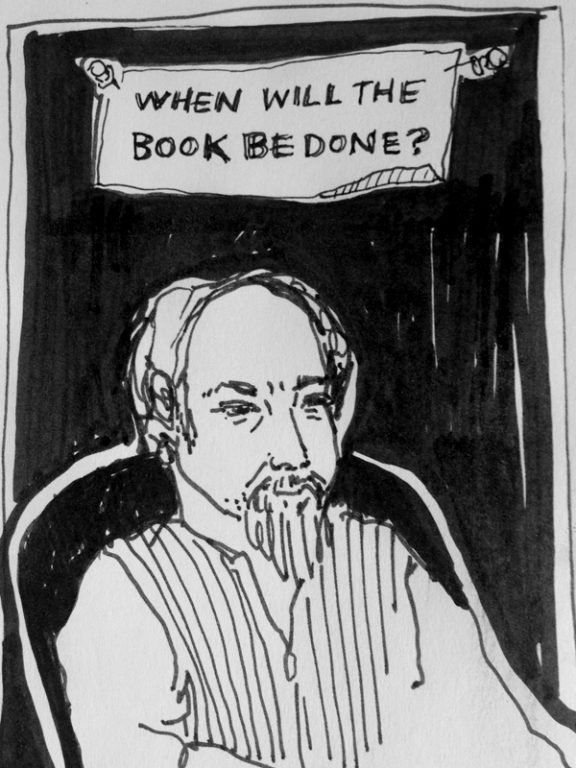

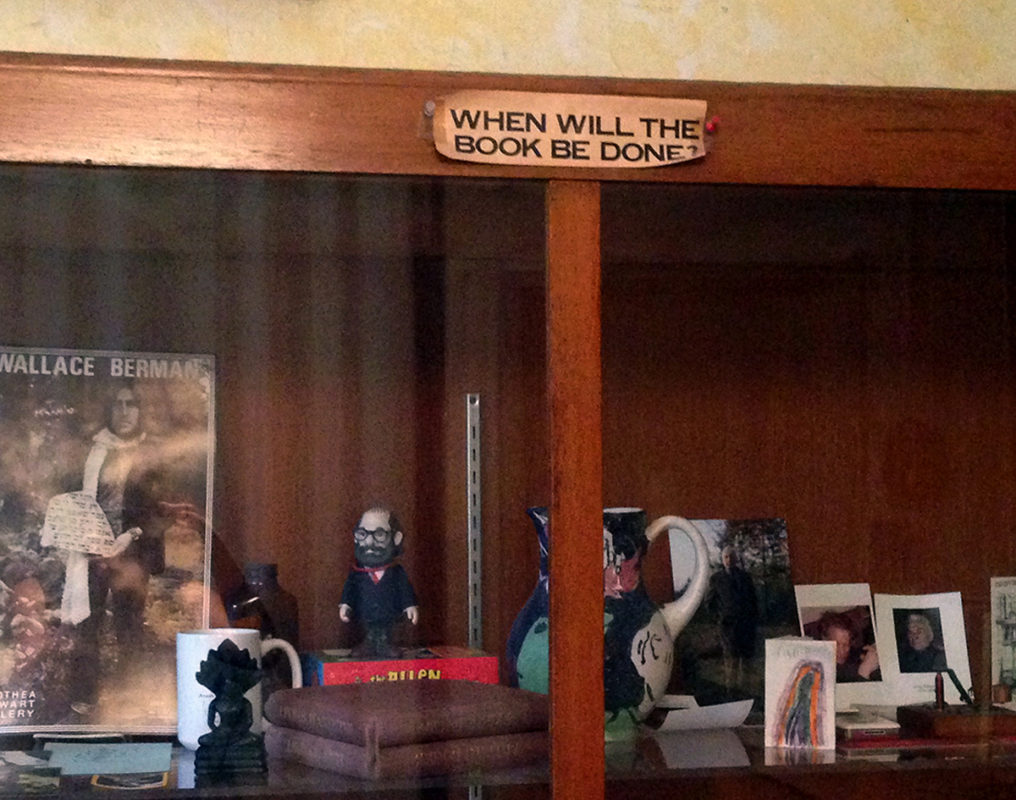

Meeting Steve in his workspace/home, I was immediately at ease. Steve is a fount of knowledge, but he’s also a genial conversationalist. I’d prepared sets of questions under several themed headings, but once we started chatting, I barely looked down. Below are notes from our conversation, and the 2001 ‘catalogue’ of Granary Books When Will The Book Be Done.

From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, Clay ran Granary as a Soho gallery space, in which exhibitions, lectures, performances, readings and book launches brought the literary and arts communities together. However, once the publishing arm of Granary gained momentum, the shopfront had to be shut down.

This illustrates the problem of being a one-person show. Initially, the idea was to continue the gallery space and publish simultaneously, each new book being launched as a show, but in Clay’s words: “it wasn’t practical to do it all.”

Clay described having 28 projects running at once in 2001 – at which point he resolved to not take on any further projects until his production schedule was caught up. Today, 2-3 projects is a manageable number.

The 1991 publication Nods was a collaboration initiated by Clay, bringing together writer John Cage with illustrator Barbara Fahrner, plus typesetter Philip Callo and binder Daniel Kelm. It’s significant that the typesetter and binder are publicly credited for their work on the book, especially with such high profile authors. This respect for the formal (material) aspects of the book is central to much of Granary’s later publishing – recognising the value of collaboration rather than always privileging the individual author.

Clay writes: “What came together in my mind quite vividly as this project concluded, were the (until then) seemingly disparate elements of publishing: words, pictures, printing, binding and distribution.”

Charles Bernstein reiterates this in the preface to When Will The Book Be Done, a 2001 catalogue of Granary’s publications, that:

At Granary, books are not neutral containers but are invested with a life of their own, conceived as objects firs and foremost, entering the world not as the discardable shell of some other story but piping their own tunes on their own instruments. Nothing is taken for granted – the binder is as much a star as the printer or writer. The design is an extension of (not secondary to) the content, just as the content is an extension of the design. For a book, a Granary book, is never about delivering information in the most expeditious form.

Asked how he brings writers and artists together – in my experience, it’s a kind of match making that can be difficult, Clay responded:

I tend to work with people who I can imagine working together. I start with the writer, ask them if they have someone they want to or are working with – often projects are already happening that I can capture at the start.

Reflecting that most artist’s books are destined to end up in libraries or special collections, which obviously limits the audience to those who can physically visit them, Clay decided to publish a series of ‘free’ books.

Do The Math, a 27 page poem by Ron Padgett with eight black and white illustrations by Trevor Winkfield, was published in an edition of 300, of which 60 are numbered and signed. Trevor, Ron and Steve each had 100 copies to distribute as they chose, sending them to friends and people they thought would enjoy the book.

Similarly, My Adventures in Fugitive Literature by Jan Herman was produced in an edition of 150. Herman tells the story of the book’s origin – Steve Clay heard him speak on a panel and asked to turn the lecture into a book.

—

Johanna Drucker:

Johanna Drucker:

writer, designer, book and alphabet historian

Ammo at Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Tuesday 21 April 2015

Johanna Drucker’s resume reads like a blueprint for my own: with an established book/graphic design practice, she turned to scholarship and continues to extend both her creative practice and scholarly writing in a symbiotic way. However, where I’m at the beginning of my academic endeavors, Drucker has written numerous seminal books and more articles than seem humanly possible on book arts, graphic design history, the alphabet, interaction design and visual studies. She works with writers, poets, artists and has been involved in the movement for design to play a central role in the emerging field of Digital Humanities. Druckworks: 40 years of books and projects was a 2012 ‘comprehensive retrospective’ exhibition of her four dozen artist’s books and other graphic work.

Where Drucker’s blueprint lays out an empire of activity, mine is currently akin to a tent city. I use Drucker as a point on the horizon to navigate toward; proof that design practice and scholarship can be done simultaneously. I look to her body of work when I feel deflated by skepticism/cynicism about the value of practitioner-research. Drucker is living proof that it can be done, elegantly rather than defensively.

Looking at some of my recent project, Johanna advised that self-referential work won’t sustain interest for long. We talked about designers in commercial practice having no content; a client to brings a project to a designer, providing the base content (the brand or book or service that needs designing) and the audience. The challenge for a commercial designer relocating to academia is figuring out what my content could be – which topics, ideas, texts or sets of material should I be working with? More challenging still is figuring out who the audience for my scholarly work is: other designers (can easily slip into self-referential territory); the publishing industry (are they interested in speculative work or theory?); other academics (again, self-referential territory when we write about design research for other design researchers, or as I have been guilty of, producing design research in an attempt to defend or argue for the value of design research).

Much of my work from the past three or four years has been self-referential while I reposition myself in academia (from commercial practice), but as I noted in the ‘Two Essays on Books’ post, the danger of responding creatively to research is that it can become overly ‘meta’: here is a print-on-demand book I made about making books using print-on-demand. Before starting any commercial design project, I always consider who the intended audience is – who does this design work need to appeal to, what language (verbal and visual) is best suited to this? The same should apply for scholarly work.

Johanna asked whether I’m positioning my work as ‘demonstration’. This makes sense to me, considering the way her work demonstrates theories (often her own) through the way it is presented or materialised.

Johanna recommended I follow up: Fred Moody’s print on demand experiment at Rice University Press. Appears to have been a short lived venture, but worth looking into for the reflections on the future of academic publishing; Max Ernst’s Maximiliana; Roger Keyes’ book EHON: The artist and the book in Japan; Emily McVarish, co-author of Graphic Design History. Emily and Johanna designed that book to the page – editing text so each spread worked aesthetically as well as textually, considering the design student audience the book was intended for. Interestingly, a new edition coming out will be designed by a new team of designers, who will alter the layout. This could go poorly.

After my conversation with Steve Clay about making books and distributing them to people you’d like to have them, I gave Johanna four of my books: Writers’ Typewriters; Words From the First Walk; Two Essays on Books; After Ed-werd Rew-shay

—

David Senior

David Senior

Bibliographer, Museum of Modern Art Library

MoMA Library, 4 W 54th St, NYC

2 April 2015

David Senior is an important figure in the artists’ book world. Beyond his enviable role as Bibliographer of MoMA, which includes selecting which artist’s books and other material the Library will acquire, David also organises the New York Art Book Fair’s The Classroom, a: “curated series of informal conversations, workshops, readings and other artist-led programs […] also an informal venue for artists, writers and publishers to feature new releases and present their publications.”

David met with me at the Manhattan branch of the Library. The first day in weeks (probably months for New Yorkers) of proper sunshine, we took the meeting to the sculpture garden.

How does the MoMA Library encourage the public to engage with their collection? David explained one strategy is making appointments accessible: by not having a set of questions to answer or lengthy forms to fill in before people can access the library, it’s a simple entry process. You email to make an appointment, or turn up to the Manhattan Library during opening hours. He also uses the NY Book Fair to reach likely researchers and artists, and runs a series of sessions with school and university classes at the Library, taking away the barrier of the unfamiliar – libraries and archives can be daunting, especially if you’ve had a bad school librarian experience. Mine was a dragon-lady who appeared to hate children.

How does the MoMA Library encourage the public to engage with their collection? David explained one strategy is making appointments accessible: by not having a set of questions to answer or lengthy forms to fill in before people can access the library, it’s a simple entry process. You email to make an appointment, or turn up to the Manhattan Library during opening hours. He also uses the NY Book Fair to reach likely researchers and artists, and runs a series of sessions with school and university classes at the Library, taking away the barrier of the unfamiliar – libraries and archives can be daunting, especially if you’ve had a bad school librarian experience. Mine was a dragon-lady who appeared to hate children.

Online presence is obviously also important now. However, as the designers at the AIGA: In the Museum lecture were bemoaning, initiating anything new in a large institution is painfully slow. To get around this David started a Tubmlr, without MoMA branding, using materials from the Library that are unlikely to cause copyright headaches by being online: exhibition invites and ephemera. He maintains the tumblr which started as a catalogue for a 2013 exhibition he organised called ‘Please Come To The Show: Invitations and event flyers from the MoMA Library’. It is a remarkable and dangerous (I lost a few hours without noticing) resource. From the Tumblr:

As an introduction to the Library’s collection of ephemera, the exhibition presents invitations relating to early projects by now-iconic artists, artists’ groups, and exhibition spaces. It also highlights some notable artists’ interventions within the format. The show itself is also an invitation, addressed to researchers, to use the Library’s collection and to seek out our ephemera files and documents that are waiting to be explored.

There is an additional site that covers more varied material. The MoMA Library Tumblr is a collection of scanned ephemera and photographs of books from the library, as well as notes from overseas trips, exhibition visits and announcements for upcoming events.

When searching the Dadabase (the Library’s online catalogue) I noticed that few artist’s books were digitised, and the few images are often only the cover. Many artist’s books have plain covers that reveal very little of the content of the book. I asked why more of the collection is not digitised.

For many reasons.Time and resources – digitisation is a slow and expensive process. I mentioned how many photographs I took of the books I looked at – what about crowd sourcing the digitisation? David said they’ve been thinking about the best ways to ‘catch’ what’s being scanned and copied in the Libraries (both the Queens and Manhattan locations have high res scanners and copy stands), but they haven’t figured out the best way to do that yet, and this leads to another issue: proprietary.

Putting high resolution images of copyright material online is dangerous. How do you manage the distribution and use of this material that the Library is a custodian of?

David said he’d love to have Every Building on the Sunset Strip digitised – not to replace the original but so ‘some kid in Wyoming who may never make it to NYC can experience that book’. The digital can’t replace the material, but it can grant access when the only other option is missing out completely.

I noted that a few of the current exhibitions in the MoMA galleries have artist’s books displayed under glass vitrines, with a digital scan of the book available to flip through on what’s probably an iPad built into the display table. This is not something the Library has anything to do with – the curators and exhibition design teams work on the gallery, and often a 3rd party vendor (out of house) comes up with the screen displays.

As David phrased it, museums and galleries work in ‘weird silos’. After an exhibition, he’s not sure where these digital copies of the books end up, but not in the catalogue (yet). The books I’m referring to mostly belong to the Prints and Drawing collection, rather than the Library.

ARTBOOK ran a terrific interview with David in 2013, in which Madeline Weisburg asks a series of questions about how artists’ books have entered the MoMA Library and how new online publications are being archived. This includes an explanation of the distinction between artists’ books/publications that belong in the Library and editions/multiples that belong in the prints and drawings department. David’s response to this question is worth re-posting in full:

That’s a really good question, and something that is a moving target in a lot of ways. There are a lot of publications that are in our collection in the library, and in the prints and drawings collection, and in the archive. So there are two or three answers for the same object. The big archive of Fluxus material that came to the Museum a few years ago has been the current example of what I think about when we discuss how things are placed in different collections. It was often an object-by-object decision, between people in the curatorial departments, the Museum archive, and the library. In the past our library collection focused on artists’ books that fell within the idea of a cheap democratic multiple, so there was an idea that if a book was made an edition of over 100 or something like that, then it became a library collected artists’ book. So that would be if the intention was for distribution and not as a scarce printed object. Sometimes that was one of the definitions of what went into the print department and what went here. So if it was a small edition of ten, or a deluxe edition book, maybe it was more appropriate in the print department than here. But there are a lot of exceptions to that within the existing collection and things we collect from artists now. One of the fun parts about my job is to meet directly with artists who actually make this stuff. I work at cultivating collections of individual artist’s work and published materials. Some things are well distributed and some things are less well distributed, but I still add it to the collection.

Another interesting distinction is embedded here: the difference between a librarian and a curator. The Library collection sits outside the Museum collection, but increasingly the line between what belongs in one or the other is blurred (the ARTBOOK interview covers this in more detail).

The Library acquisition differs from curating. David says “my interest and taste doesn’t dictate what we collect, it’s more about getting a sense of what’s happening, internationally. We skew towards small scale stuff.” His decisions are also dictated by budget – his inclination is toward acquiring more less expensive items over one big thing.

Two other interviews with David that are worth reading are with the Library as Incubator project and the Blouin Art Info site.

–

Shana Agid

Shana Agid

Book maker and scholar

Thursday 8 April 2015

The City Bakery, W18th St NYC

With a background in printmaking and book arts, Shana Agid is Assistant Professor of Art, Media and Communication at Parsons School of Design, and currently finishing a doctoral thesis at RMIT.

Shana suggested meeting at The City Bakery. An excellent choice, though I went into a sugar coma after a hot chocolate which was actually a bowl of cocoa-fondu. Over an hour or so, we had a great chat about design research, book making as a kind of critique, the way materials affect our design process and thinking, and parted with the suggestion of a book/printmaking project between UTS and Parsons.

Returning to my apartment, I looked through projects on Shana’s website, Rind Press

Shana’s 2012 map-fold book Call a Wrecking Ball to Make a Window was produced during a residency at the Minnesota Center for Book Arts. The book uses a map of NYC as a base for layering stories about the lives of gay men from the 1970s through 2000s, and uses the writings of David Wojnarowicz as a ‘window’ through which Shana traces a personal narrative.

The book folds out like a street map, and is typeset around a map. This format draws our attention to NYC as a backdrop and a structural device for the narrative:

Manhattan is thirteen and a half miles long and, at its widest point, just three miles wide. It can be gotten around by boat in three hours and by foot in less than a day. It is, geographically speaking, a small and navigable place; despite this, it is a monster of a city. It is a good landscape for telling impossible stories.

On the site a slideshow of images shows the design process, and a video of a recorded artist talk gives further context to the work. There’s also a great interview. An excellent example of how to frame a design project in a research context by articulating the context of the work, and insights drawn from the creative process.

This book (is it a book if it isn’t a set of pages bound along one edge?) is the kind of book project I’ve been hunting – book making as a response to another writer/artist’s work. It’s not a illustrated edition of David Wojnarowicz’s writing, or a homage to his work (or if so, only incidentally). It is an entirely new work that, through the process of its conception and production, lead the researcher/designer to a better understanding of both the subject matter and his/her own practice.

That Shana chose to produce the work using letterpress – a slow and messy process – is significant. The time it takes to produce the work after the design has been completed means the project stays in the hands of the creator right until the end. In a commercial project, I send digital files to a printer, the final work appears magically finished, but without my input in the phase where it becomes a tangible entity in the world.

–

One-hour coffee meetings

New York City

March – April 2015

When on the other side of the world, it seems crazy not to email people whose writing or design practice you admire and ask for a coffee meeting.

Cameron Tonkinwise

Director of Design Studies, Carnegie Melon

Cameron was my PhD supervisor for the first year, and I will never forget him drawing a triangle on a post-it note and saying ‘this is your thesis’. I can’t remember what the three points were now, but he was probably correct. He’s a very smart man. We met at Blue Bottle Cafe in Williamsburg – Cameron was indignant that he’d taken me to best coffee shop in Brooklyn and I ordered a green tea. To be fair, it was a luminous – shockingly luminous – green matcha tea, organically something and free of everything. We talked about design research and the future of academic publishing: the importance of showing as well as telling (the Media Object series as an example, but also people starting up small publishing experiments and using online platforms like Academia.com or Linked In to disseminate research outside the traditional academic publishing model).

Timo Rissanen,

Parsons the New School for Design

This almost doesn’t count because Timo is a close friend, but we’ve been talking for years about doing a bird project together. I’m writing this here to publicly shame us into action. Since heading to NYC, Timo has been publishing and working on practice-led research projects in a way that makes me exhausted to think about. Just for fun he’s also taken up marathon running. Up mountains. We went to see the New Territories show at the Museum of Arts and Design. It was ok, but a strong reminder to pull back on the jargon. We also went to MoMA PS1 and played a fun game of ’is that an artwork?’

George Plionis

Jeweller, 3D whiz

As with Timo, George almost doesn’t count as a research meeting because of the friendship, however I collaborated with George in 2014 to design a print-on-demand catalogue for his solo show in NYC, Mariposa. George is starting a new collaboration with a Sydney-based jeweller, and we discussed me coming on board to design a more complex catalogue for this 2016/17 show.