What is a book in the digital age?

As a professional book designer, I’ve spent a decade observing electronic books from a cagey distance. A couple of years ago, I reluctantly recognised the need to engage with these alien book forms, both as a reader and a designer. It is the 21st century.

What I have come to realise is this: electronic books can do certain things that print books cannot, and therein lies their value. Enhanced electronic books are changing our definition and expectations of books.

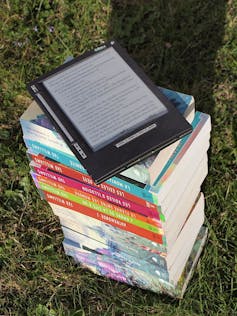

My office, home and handbag are still stuffed with print books; eBooks (e for electronic) have not replaced pBooks (p for print) in my life. I find myself toggling between the two.

I consider the relationships between print and electronic books from the perspective of a reader and designer. What are these different formats, and how do they affect the way we produce and consume content?

The smell and feel of paper

Let’s get nostalgia out of the way quickly. Print books have a material quality that electronic books do not. For many of us, the intimacy of cradling a book close to our chest, hanging our head over it and shutting out the real world is a sacred ritual. The smell and feel of paper can never be replicated by a cold, hard screen.

Although it’s possible to read an electronic book in a bath, it’s less relaxing and more dangerous (not in a fun way). Browsing a bookstore or library and flicking through books is a social, embodied experience. Clicking on a screen is not.

Amazon.com has a complex algorithm to suggest books I may like based on previous purchases, but I’d rather have a librarian or bookseller make suggestions based on their expertise and a conversation, and walk out holding the book object. The tactile differences between page and screen will always be an issue for those of us raised on ink and paper.

But watch how a toddler tapping stubbornly at a magazine becomes annoyed that the image isn’t changing. That child is unlikely to feel the same nostalgia for print as her parents, because her understanding of “book” will be significantly different to theirs.

The technology we use to present and consume information has changed. The toddler who understands that tapping a glassy surface should make an image change demonstrates that technology is developing at an unprecedented rate, and unless we are constantly attentive we risk being left behind.

New tech, new challenges

Although often linked, anxiety about the new is different than nostalgia for the old.

A print book is a beautifully simple technology to use. Pick the thing up, turn each leaf in sequence until finished. If literate, anyone can pick up and read any print book.

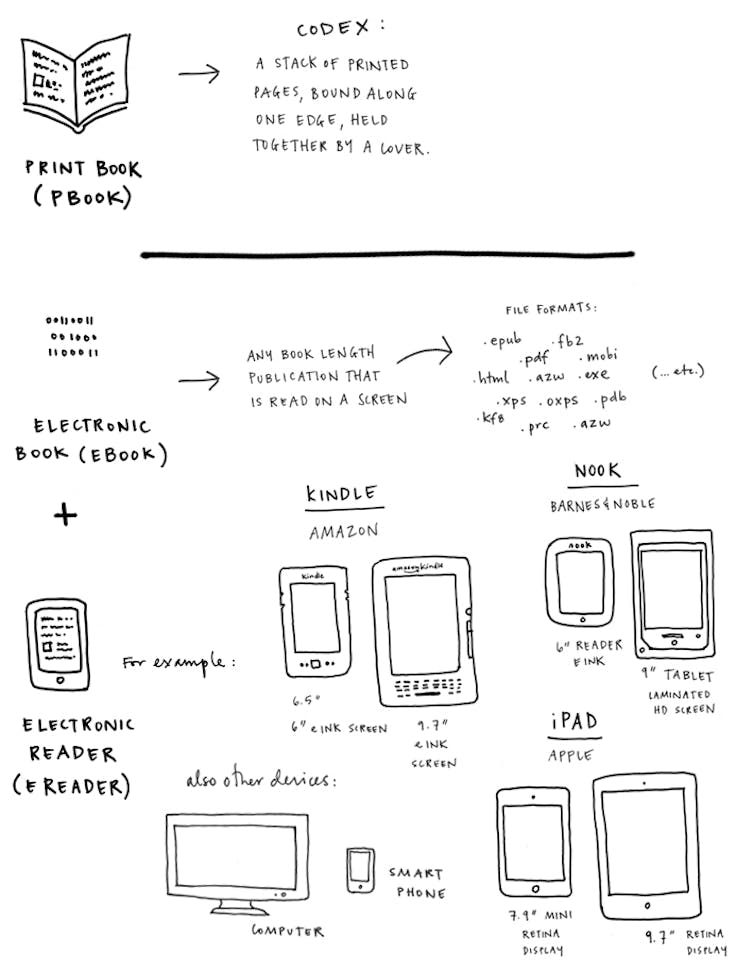

An electronic book is a more complex technology. An eBook requires a computer, eReader or tablet, and a power source to keep the device charged. It requires computer access to a website or digital catalogue where files can be downloaded, and an understanding of how to use it.

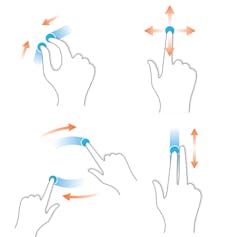

Pages aren’t just turned, they are clicked and pinched and swiped – movements that need to be learned, and vary between different devices and brands.

In other words, you need new kinds of literacy to even get to the text. Moreover, you need to keep up with constant development and updating of these devices and programs, and understand the value and limitations of different devices, formats and suppliers.

This market-driven mess is the major issue with current eBooks. Different eReaders are made by different companies – Amazon’s Kindle, Barnes & Noble’s Nook and the Sony Reader, to name a few. Then there are tablets, such as Apple’s iPad, which perform a range of functions similar to a computer, one of which is enabling users to read eBooks through an app (short for “application”, or computer program).

These different devices run on different software, and require different file types. An eBook that works on a Kindle may not work on an iPad. There is no single file type that allows an eBook to be published all devices.

So although cutting out the printing and binding process of traditional book production may seem to reduce production time and costs, the confusion of designing for different platforms and devices means an entirely new and more complicated production process has been introduced.

Amazon’s Kindle Fire eReader, released just before Christmas 2011, was riddled with bugs and problems: volume-control glitches, an off-switch that was easily hit by accident, slow loading time and an unresponsive touch screen. Hundreds of articles and forums are dedicated to problems associated with iPads: overheating devices, Wi-Fi connectivity issues, slow charging, apps and eBooks refusing to sync or download.

This can seem overwhelming when you could just pick up a print book and begin reading immediately.

Yet the complexity of the digital system is what allows eBooks to do astounding things, and offers versatility and accessibility impossible in print.

More pros than cons

The most immediate appeal of eBooks for digitally-reluctant readers is the efficiency afforded by an eReader. Packing for a vacation, a single device the width of a novella that contains hundreds of books is incredibly convenient and offers a previously unimagined variety of instantaneous choice.

Travelling on the Trans-Mongolian Rail a few years ago, I constantly cursed the bulk of Anna Karenina. With an eReader, I could have slipped Tolstoy’s entire oeuvre into my jacket pocket, with some Dostoyevsky for good measure. Then again, finding a power source in a yurt would have proved problematic.

Other appealing aspects of eBooks are immediacy and variety. Incredible numbers of eBooks, including many that are difficult to find in print, are available instantly from repositories, with no delivery time, and with many at a lower cost than print books.

The US-based online literary archive Project Gutenberg has more than 42,000 free eBooks – digitised books that have fallen out of copyright.

Most publishers offer new releases in both print and electronic editions simultaneously. These eBooks are direct translations of print books; the same text is scanned in, or typeset for an eReader, exactly as it would appear in the print edition. For those direct translations, the difference between a print and electronic edition is a matter of the reader’s preference. The content of the book is the same, only the format differs.

A richer reading experience

A more curious breed are “enhanced eBooks”, which include audio-visual and interactive elements such as short videos and animations.

UK company Touch Press are leading that field. Their titles include an edition of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land that contains a scanned draft of the manuscript hand-edited by Ezra Pound, an original video performance of the poem, and a suite of video interviews with poets, theatre directors and scholars discussing the cultural significance of the poem.

They have also produced an edition of Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings that allows users to zoom at extraordinary resolution and compare Leonardo’s theories against modern knowledge with 3D models of human anatomy, as well as interactive demonstrations.

Touch Press is also behind an animated, annotated periodic table of elements that has to be seen to be believed. Their highly interactive release, Gems and Jewels, allows users to rotate the pictures within the books to see the other side.

Touch Press’ website manifesto reads:

Books are one of the defining inventions of civilisation. Today publishing is being transformed by digital technologies. The aim of Touch Press is to create new kinds of books that re-invent the reading experience by offering information that is enhanced with rich media and that adapts dynamically to the interests and experience of the reader.

These kinds of publications are different than the eBooks that are straight translations from print to digital. They include audio-visual and interactive elements that cannot be reproduced on the page.

These are the eBooks that are changing the way we consider what a book is, and could be.

This is a foundation essay for The Conversation’s Arts + Culture section. If you are an academic or researcher with relevant expertise and would like to respond to this article, please use our pitch facility.

Zoe Sadokierski, Senior Lecturer, School of Design, University of Technology Sydney

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.