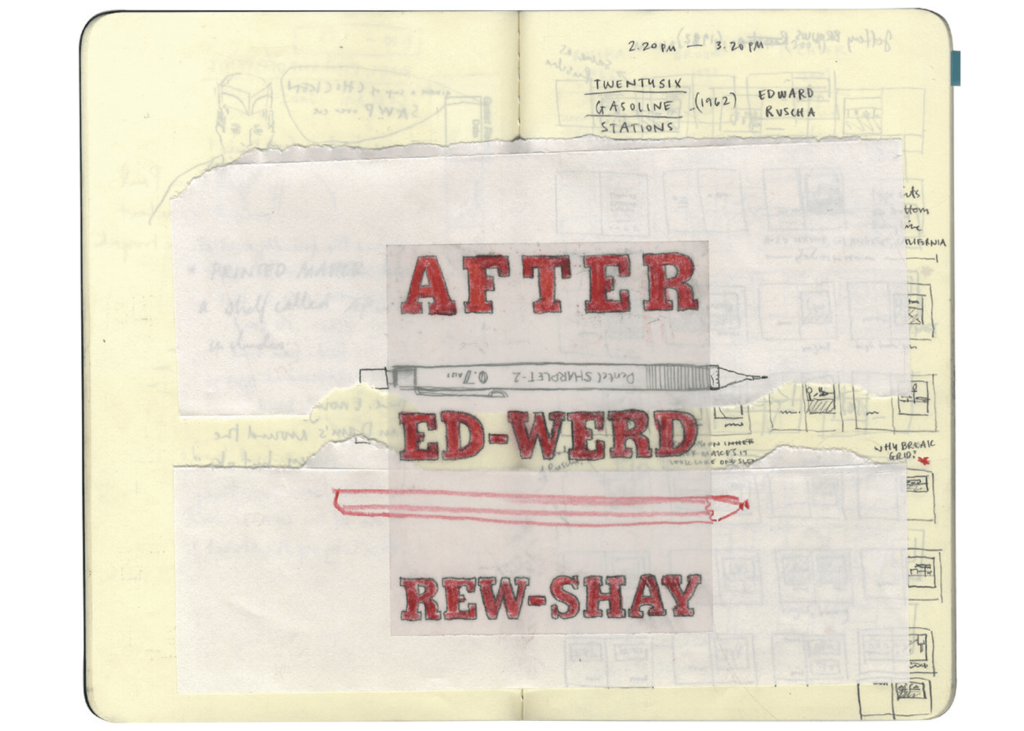

After Ed-werd Rew-shay

(Another Book) After Ed-werd Rew-shay

Written, illustrated and designed in one week by Zoë Sadokierski.

Printed on the Espresso Book Machine in about 5 minutes, at McNally Jackson bookstore. 52 Prince Street, NYC.

68pp paperback, A5 (148 x 210mm)

Mono interior, colour cover

Edition of 5, two proof copies

This book documents my research at the MoMA Library, looking at Edward Ruscha’s artist’s books (among other things). The strange spelling of Ruscha’s commonly mispronounced surname (I thought it was Rush-ah) comes from the title of one of his 1972 catalogue/books: Edward Ruscha (Ed-werd Rew-shay) young artist. More on that in the essay below.

The book itself is an experiment in publishing using print-on-demand technology. I’ve previously written about and created a suite of books using online print-on-demand platforms such as Blurb.com and Lulu.com, but the production of this book was different: it was created almost instantly, on a printing and binding machine that sits in a bookstore. From when the bookstore clerk hit print to when the book arrived in my hands, still warm, was a little under 5 minutes.

I watched this machine print and collate the pages, glue bind the cover on and crop the book to the size I specified. Magical.

Excuse the poor quality of the photographs below – on the road I’m working with limited tools: an iPhone, natural light and a laptop.

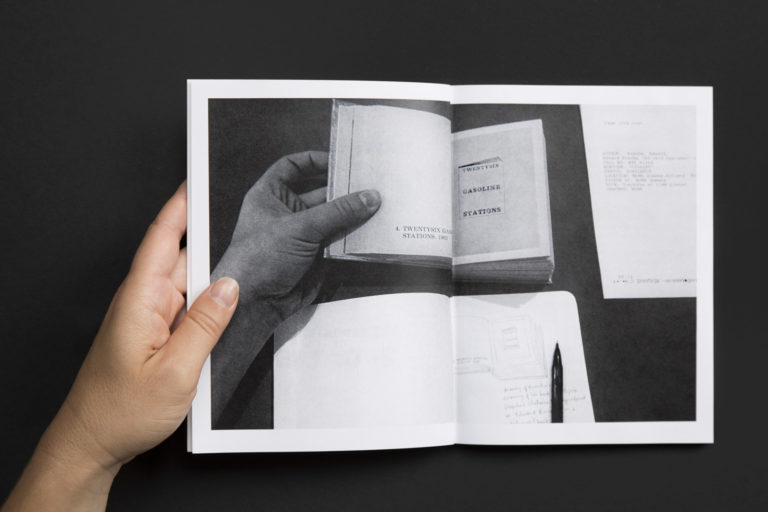

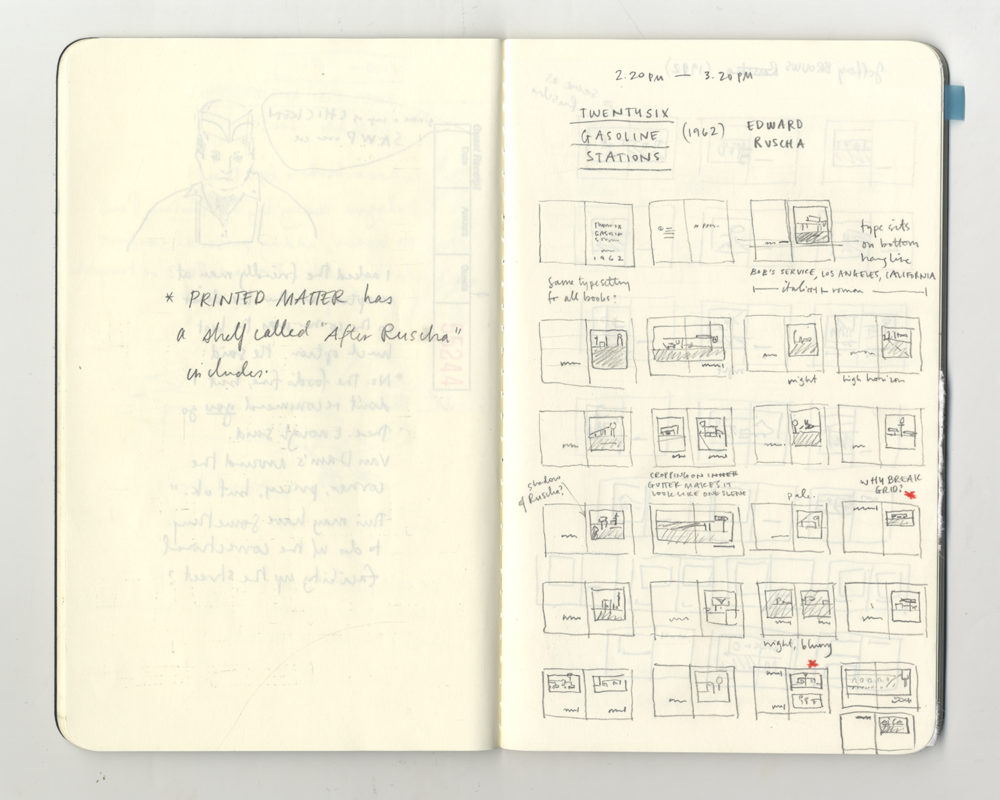

Process sketches and notes:

Below is the essay I wrote to introduce the visual essay ’26 Views from the 7 Train’ which makes up the body of the book.

This book was always meant to exist, but it wasn’t supposed to be about Edward Ruscha. To explain how the book came to be, I need to back up. Make yourself a cup of tea, this may take a while.

Book Machines

I came to New York for five weeks over March-April 2015 for two reasons. Primarily to research the history of artists’ books and independent (small press) publishing. I’ve been producing artist’s books for more than a decade, though in order to discuss my bookwork in an academic context – which my job as a university lecturer requires me to do – I need a scholarly understanding of the field. New York, with a diverse independent publishing culture and a wealth of research libraries, is an ideal place to develop this understanding.

The second reason I came to New York was to produce a book on McNally Jackson’s Espresso Book Machine. During a visit in 2013 I discovered that McNally Jackson has a clever little machine, between the magazine section of the bookstore and their café, that can print, collate, cover and bind a book in a matter of minutes. In theory, in the time it takes to have a cup of coffee. Magical.

There are Espresso Book Machines all over the world, according to a list on the manufacturers website: Canada (11); Dominican Republic (1); Egypt (3); France (6); Japan (2); Netherlands (2); Philippines (1); UAE (2); USA (38). Disappointingly, none in Australia. So I vowed to return to New York and make a book. Here I am.

For the past couple of years I’ve been experimenting with ways to independently publish books using different print-on-demand platforms. Print-on-demand is a digital printing service that allows anyone with a computer and credit card to publish a book in editions as small as a single copy. The process is simple: the author uploads digital files of the book pages and cover to an online platform (a print-on-demand supplier such as Blurb.com or Lulu.com), then when someone orders a copy, the book is printed and posted to them, anywhere in the world.

Print-on-demand means an author can publish a book without spending money other than the cost of ordering a single proof copy – as little as a few dollars. When someone orders a copy of the book online, the author receives royalties. No initial financial outlay for the print-run, no warehousing and distribution cost or management. It goes without saying that this is a game-changer for the book publishing industry.

Print-on-demand technology (and the internet) enabled me to launch my own small publishing venture, Page Screen Books. Many similar small presses are mushrooming up around the world. There is a clear parallel between the current small press movement and what was happening in the art publishing world around the time Edward Ruscha was producing his ‘democratic multiples’ in the early 1960s and 70s – but we’ll come to Ruscha shortly.

For me, the appeal of the Espresso Book Machine, in contrast to the internet print-on-demand suppliers I’ve previously used, is that I can watch my book being made. Using an online supplier, my book could be printed anywhere in the world and the turnaround from ordering a book to it arriving at my door is between three days and three weeks. The Espresso Book Machine promises about three minutes, and I can watch and listen to it come into being.

From Sydney, I planned to document my time in New York through writing, drawing and photography, to generate content for a print-on-demand book I would produce before leaving. I had an idea for a theme or structure that would be a typology of New Yorks based on writing by E.B. White and Liz Danzico. But this idea was abandoned when I found Ruscha in the MoMA archives, and everywhere else I looked.

Archival Digs

Back to my primary reason for being in New York – researching artists’ books and the small press movement. I wanted to spend time considering ways other artists employ or exploit the book form in order to reflect on my own bookmaking practice. Although there are many excellent publications and online resources which document the field of artist’s books , to truly appreciate an individual artist’s book you need to experience it in person.

The book is a intimate form. We cradle a book in our hands, hold it close to our chest and hang our heads over it. The size and shape of the book, its weight, the paper stock, the quality of printing and design all affect our reading experience. Usually, we read alone. When we’re ready, we turn the pages sequentially to move ahead.

Artists who work in book form play with these factors: within an artist’s book, the format may convey more information than the written text (if there is any written text at all); paper stock may indicate how to navigate the story; the next page may reveal something entirely unexpected. To understand an artist’s book, you need to experience it in its original form.

To begin my research, I arranged visits to the Museum of Modern Art library. The artists’ book collection is primarily held in the MoMA QNS building, which is only open to researchers on Mondays between 11am and 5pm. The library holdings include about 300,000 books and exhibition catalogues. With limited time and limitless possibilities, I needed to start somewhere.

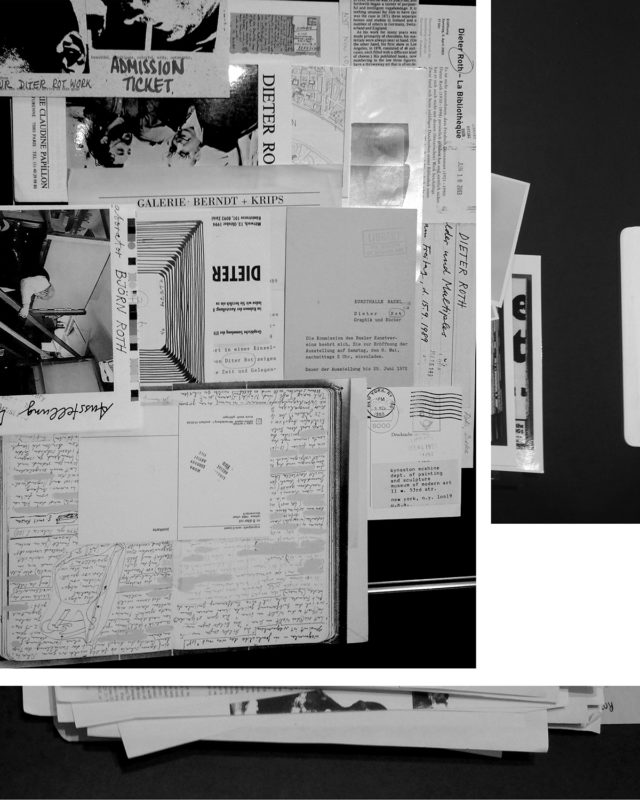

Johanna Drucker’s seminal book The Century of Artists’ Books cites the post-war artists Dieter Roth and Edward Ruscha as key figures in the history of artists’ books. Both artists made series of projects exploring the potential of producing artworks in book form, and moreover, “Roth and Ruscha also serve conveniently to contrast the two distinct attitudes toward artists’ books as an inexpensive edition or democratic multiple.” (71)

I began with Dieter Roth. Drucker describes Roth as an artist working with the book as a physical form, playing with structural investigations of the book. Roth layers pages and images of pages to create patterns and new compositions within his books. In the front matter of his book Snow, Roth provides a typewritten page with:

A few of the successfull (sic) recipes

offered by Rot (sic) in this Volume:

ON THE VISUAL ARTS

“ Take a thing and put it on one thing

Take a thing and put I on the 2 things

Take a thing and put I on the 3 things

Take a thing and put I on the 4 things

Take a thing and put I on the 5 things

Take a thing and put I on the 6 things

Take a thing and put I on the 7 things

. . . . . . . . . .

sell any time

Using ephemera from the Franklin Furnace Artist File of Miscellaneous Uncatalogued Material for Roth, I followed his instructions:

In my studio at home, I have a folder of abandoned photocopies salvaged from the bin at work. I kept the edges, where the pages of the book and its cover creep into the blackness of negative photocopier space. Sometimes there’s a wrist and the heel of a hand, evidence of the person photocopying pressing the book into the glass. I use these scraps in collages. I get Roth.

From Roth, I moved to Edward Ruscha. Drucker argues that in contrast to Roth’s use of the book as “an art work – not a publication or vehicle for literary or visual expression, but as a form in itself”, Ruscha uses the book in an “almost neutral manner, or at least, in a manner designed to neutralize the physical and structural features of his books by making them as conventional and inconspicuous in material terms as possible.” (75)

Ruscha’s bookwork is distinct in that many of his publications follow similar formal and aesthetic constraints: 5.5 x 7 inch portrait format; white cover; title typeset over three lines in typeface Stymie, all caps, the lines aligned top, centre and bottom of the page. Internally, the books feature black and white photography, occasionally treated with a yellow tint. Thematically, the books document typologies of ordinary urban things and spaces: gas stations, car parks, swimming pools, apartments, streets.

The first book I encountered was a small, Kelly green brick of a book titled Edward Ruscha (Ed-werd Rew-Shay) Young Artist. The title page states that the book accompanied an exhibition of prints, drawings, and books held at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1972. Printed on brown kraft paper, it is a confusing and engaging little unit. I’m not ready to talk about this book yet, but I’ll certainly come back to it some other time.

Ruscha’s Twenty-six Gasoline Stations is widely cited as the first example of artist’s bookmaking. Searching for Ruscha in MoMA’s ‘DADAbase’ (digital catalogue), I noticed several books listed by other artists with the same title as Ruscha’s. A worm hole appeared and I crawled into it.

My research plan was to dip into Roth and Ruscha’s work quickly, as I’d dip a toe into a body of water to prepare for full immersion. I had lists of other books to investigate – and I did, over two additional sessions at the library – but something about Ruscha’s work kept drawing me back.

One afternoon at the New York Public Library, in the exhibition ‘Public Eye: 175 Years of Sharing Photography’, Ruscha’s expansive concertina book Every Building on the Sunset Strip was waiting for me. On a day trip to Princeton, a large work on paper titled ‘Survey Map of South Bunker Hill Area of Los Angeles, about 1956’ from the Huntington Library reminded me of Ruscha, then I turned the corner and another copy of Every Building on the Sunset Strip was waiting for me. At the Gagosian shop, a vitrine held an almost complete selection of Ruscha’s books. A label taped to shelf Chelsea bookstore Printed Matter read ‘After Ruscha’; the shelf hosted a cluster of books made in homage to Ruscha.

More than Ruscha’s work itself, I am fascinated by these homage books. In 2013, MIT press published Various Small Books: Referencing Various Small Books by Ed Ruscha. The book collates ninety-one projects by artists who have appropriated or paid homage to Ruscha’s books, and includes an appendix listing all known Ruscha book tributes. Included are projects in which artists rephotograph Ruscha’s work – such as Thirtyfour Parking Lots, Forty Years Later (Susan Porteous 2007) – or riff off his conceptual and formal template – Various Unbaked Cookies and Milk (Marcella Hackbardt 2010).

Drucker mentions one of these: “The parody by Jeffrey Brouws demonstrates the cult status of Ruscha’s books among artists’ books.” (77) Parody implies the mimicry is done for comic or satirical effect. I sense there’s something more than that happening here.

To think this through, I chose two homage Gasoline books to look at closely in relation to Ruscha’s original: Brouws’ 1992 publication Twenty-six Abandoned Gasoline Stations, mentioned above, and Michalis Pichler’s 2009 Twentysix Gasoline Stations.

I started by thumbnailing Ruscha’s book, followed by the other two. This is a technique I use to help me analyse the way each page of a book is composed, and the way the sequence of pages contains rhythms or surprises. Usually, you thumbnail to figure out how to design a book, but I find the reverse gives a particular perspective for analysing a book. By drawing each page, I slip into a kind of design trance that helps me look closely and purposefully.

I also use these thumbnail maps to compare the books to each other.

Brouws follows Ruscha’s template exactly – using black and white photographs and mimicking the alternating square and rectangle images, and exact composition for each double page spread. The half-title page dedicates the book to Ruscha. A loose, translucent sheet inserted in the back of the book reads:

In late twentieth century postmodern America the number of gasoline stations across the nation has dwindled. With rising land values and new, tougher environmental restraints, many independent station owners found themselves unable to replace aging underground tanks that the EPA deemed unsafe. Subsequently, a favorite public place where flat tires were fixed and the weather discussed, is slowly vanishing from our landscape.

Brouws book is an homage to Ruscha, but it also extends the original book by overtly layering additional information. The addition of ‘abandoned’ to the title signals that there is something more to this book than a direct copy. The sheet of paper at the end makes this explicit. Brouws takes a familiar book and slightly subverts it, to communicate a point.

Pilchler’s book follows the formal and aesthetic pattern of Ruscha’s book less closely, and is less clear in its intention. The photographs are printed in colour and all depict the ‘same’ station in different locations – a chain of generic German gas stations that follow an architectural template. There are only sixteen stations photographed. A seventeenth photograph shows a hand holding a white card printed with the statement: “The eccentric stations were the first ones I threw out.” The caption to the image reads: “Some words in a line instead of some missing stations.”

I read Pilcher’s book as comment on the uniformity of contemporary German gasoline stations; the stations are visually similar, and Pilcher tells us he has deliberately omitted ‘eccentric’ stations. I suspect there is more going on – Rushca uses cards printed with text in other books.

Where Brouws follows Ruscha’s original remarkably closely and spells out his intention, Pilcher borrows the general idea and follows Ruscha’s form only loosely.

As Drucker compared Dieter Roth and Ed Ruscha’s bookmaking to demonstrate different approaches to using the book as an art form, I compare these books as different approaches to bookwork homages. The inevitable next step was making my own.

Twenty-six views from the 7-train

I have taken prosaic photographs from train windows for years. During a three-week journey on the Trans-Mongolian Rail from Beijing to St Petersburg I captured thousands blurry landscapes and desolate train platforms. Like almost everyone else with a camera and a history that involves air travel, I also have collections of airplane window snapshots: cloudscapes, sunsets cut diagonally by a plane wing, city grids.

I began this train window series on my way home from my first MoMA library session, before I thought of making this book. I was inspired, alert, overwhelmed after a day of intense study, and I took the photos as a way to channel my fidgety energy. It occurred to me later that this was the closest thing to Ruscha’s theme as I was going to be able to pull off in the week between deciding to make the book and printing it.

Ruscha’s Twenty-six Gasoline Stations follows Route 66 between Oklahoma and Los Angeles. Twenty-six Views from the 7 Train follows the train route between the MoMA QNS Library and my (temporary) apartment.

Ruscha’s book documents gas stations; markers along a lengthy and often monotonous stretch of road. Although some shots appear to be taken at speed, for the most part the stations are stops on a familiar journey – this was a road Ruscha traveled frequently between his home town and his adopted home of LA.

My photographs capture whatever was outside when I had a clear shot of the train window, which was infrequent, especially in peak hours. Unlike Ruscha, the landscape is unfamiliar to me, even after three return trips (plus additional trips on the same train line to visit friends in Queens).

Ruscha produced his books using the cheapest, most convenient printing available to him. At the time, that was offset printing. He visited the press – the story goes that he changed the layout 50 times at the printer.

I will produce this book tomorrow using the cheapest, most convenient printing option available to me. This is the Espresso Book Machine at McNally Jackson, on Prince Street in SOHO.

This book was conceived, written, designed and produced in a week. I think the 1962 version of Ed Ruscha would be pleased it’s come to this.

———

1 The company behind the machine is On Demand Books, founded in 2008 by Jason Epstein (former Editorial Director of Random House and co-founder of the New York Review of Books), Dane Neller (former CEO of Dean & Deluca) and Thor Sigvaldson (background in advanced technology).

2 In my 2014 exhibition ‘Books On Demand’, I displayed 12 illustrated books I created and published using different print-on-demand services (primarily Blurb and Lulu).

3 Writing this now, I wonder if in a year or so explaining print-on-demand books will seem like explaining where milk comes from – something only wilfully naïve people will not know.

4 Bookwork publishes visual essays, with an emphasis on integrating design and illustration (photographic, typographic, illustrative) within the primary text to create complex reading experiences. www.bookworkpress.com

5 It should be noted that most stores have a waiting list of several days for the books to be printed, due to file checking and a back-log of orders. And although I can’t imagine not wanting to watch the machine at work, others may just want their book.

6 As a start see: The Century of Artists’ Books, Johanna Drucker (1994/2004); Booktrek: Selected Essays on Artists’ Books since 1972, Clive Phillpot (2013); A Book of the Book, eds. Steven Clay and Jerome Rothenberg (2000).